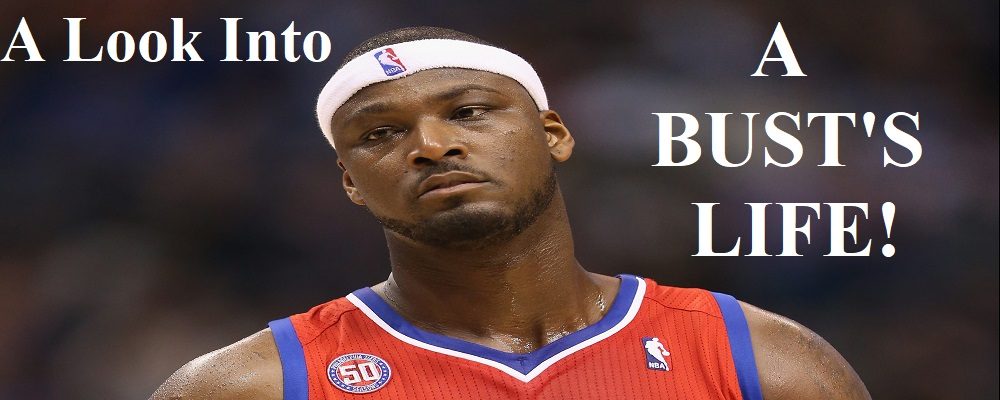

The True Story Of Kwame Brown ‘A LOOK INTO A BUSTS LIFE’ As Written By A White Woman Named Sally Jenkins!

by Tj Sotomayor August 23, 2021 0 commentsThis May Be The Issue!

By: Tommy “Tj” Sotomayor

By Sally JenkinsApril 21, 2002

Kwame Brown knows more than he should about some things, such as certain aspects of human nature, and less than he should about others, such as nutrition, how to treat a good suit, and when to throw the lob pass. What Brown knows and what he doesn’t is a consequence of his age, newly 20, and where he’s from, the saw grass lowlands of Georgia, where crook-armed silhouettes of shrimp boats move against the horizon and misshapen oaks draped with gothic-gray moss line the melting tar streets, so sticky-hot that the children, Brown until recently one of them, hitch up their pants and hop from patch of grass to patch of grass.

Brown’s route to the National Basketball Association has been a similarly awkward hop, from an overcrowded home with a sagging porch in Brunswick, Ga., to the $11.9 million patch of grass offered him by the Washington Wizards last June, when Michael Jordan made him the NBA’s No. 1 draft pick and gave him a three-year contract. The presumption behind this investment is that Brown will become another Kobe Bryant or Kevin Garnett, the next great young thing. The truth is that, in practice, the hop is too big: Turning a teenager from a sleepy shrimp port, not long out of puberty, into a multimillionaire NBA professional is a traumatic process. And not just for Brown, either. For the adults, too.

Brown has been lectured and scolded and instructed, advised. And, perhaps, warped. The voices have overwhelmed him. They run together, all of them telling him what is best for him. “Most people,” he says, “are wrong.” He is still young enough to have a faintly wounded set to his jaw, and a reflexive honesty as he considers a rookie season that, until the very end, was a public humiliation. “There’s a part of me that questions, when your confidence drops like mine did, are you a good ballplayer and do you deserve to be here, or what?” he says. “You’re just scared. Scared to do anything.”

Brown is sitting in Clyde’s restaurant in Chevy Chase, regarding with suspicion a chicken sandwich, which has been served to him on unfamiliar bread. Among the many revelations of his profoundly dislocating and confusing rookie season with the Wizards are the things that some people will eat.

On a road trip to Boston, the Wizards took him to an elegant French restaurant. Brown was not just shocked, but outraged, to discover that the restaurant did not serve French dressing. “Can you believe that?” he says. “No French dressing. In a French restaurant.”

Then there was the matter of the salad itself. “It was tree roots,” he says disgustedly. “Leaves. And branches.”

For weeks afterward, Brown took a bottle of store-bought French dressing with him whenever he went out to dinner.

On this particular day Brown is having lunch at Clyde’s with Duane Ferrell, a retired 13-year NBA veteran who has been hired by the Wizards to mentor him through his first season, and Maureen Nasser, their director of public relations.

A plate of strangely shaped fried seafood arrives at the table.

“Is that like fried shrimp?” he asks.

“That’s calamari,” Nasser says. “It’s squid.”

“You shouldn’t have told him that,” Ferrell says.

Brown looks stricken.

“Squid,” he repeats.

“You should have just let him eat it,” Ferrell says with a laugh.

What Brown knows, and what he does not, has been a source of continual surprise for the Wizards, and they have not always been amusing surprises, either. The fact is, when Jordan, in his role as the team’s chief executive, and Coach Doug Collins decided to make a 19-year-old fresh from his senior prom at Glynn Academy the No. 1 draft pick, they had no idea what they were actually getting themselves into. Isiah Thomas, the head coach of the Indiana Pacers, tried to tell them. “You’re going to be shocked,” Thomas said. “He won’t know a thing about basketball.”

Basketball was the least of it. With Brown, the Wizards have found themselves in the business of child rearing, of caring for a 6-foot-11 baby-man who has required far more careful handling and feeding than they bargained for.

He fooled them. The Wizards’ youngest player only looked fully formed. The problem was Brown’s deceptive physique; he seemed so ready-made. He was beautiful, they all agreed, your eye couldn’t help but go to him, in everything he did, just picking up the ball. He was lightning quick for a big man, and he could handle the ball, which meant he could make a play the length of the floor. “Skills people dream about,” Collins says. When he worked out against fellow high schooler Tyson Chandler, he had no conscience whatsoever, which was what they liked most; he was reckless and unschooled and he decimated Chandler in one on one, and oh, they’d seen things like this before, hadn’t they, and what it was, well, it was the real thing.

And he seemed so level-headed, smart and self-assured. “If you draft me, I’ll never disappoint you,” he told Jordan.

“He’s mature, articulate, he’s 6-11, and got all this talent, and you think he’s ready to help us immediately,” Collins says. What they couldn’t see was the inside of him. The lungs that were underdeveloped. The softness that came from never having been really pushed, from not having lived alone in a big city, from never having been away from his mother. “Inside, he’s mush,” says his youth pastor from Brunswick, the Rev. John Williams.

There was the time they discovered that he was eating Popeyes fried chicken for every meal, including breakfast, because he didn’t really know how to grocery-shop. The sports management firm that represents Brown, SFX, assigned Richard J. Lopez, a 36-year-old business manager, to shepherd him. Lopez found that he essentially became a parent.

Lopez took Brown to a Giant supermarket and helped him fill a cart with food. Then Lopez drove Brown home to his rented apartment in Alexandria and hard-boiled a dozen eggs for him and put them in the refrigerator.

One morning before a Wizards game, Brown called Lopez, and said, “I have nothing to wear. Everything’s dirty.”

Lopez knew Brown had a closet full of new suits — he had helped hang them there. “Kwame,” he explained, “you have to take those suits to the dry cleaners.” That was fine, Brown said, but he didn’t know how to do that, and he still didn’t have anything to wear.

Lopez drove over to Brown’s apartment, and found the suits in a heap by the bed. Each time Brown wore one, he would take it off, wad it up and throw it in a corner.

Lopez picked up a suit from the pile, got out the iron, and began ironing.

It was Lopez who helped Brown find his apartment, a four-bedroom condo in Alexandria. Lopez also got him a deal on a Mercedes S500, and a free cell phone, and helped him set up his cable service, and get an ATM card, and all the other things that go with being an adult. At first, Brown’s mother, Joyce, was there to help, and there was a temporary roommate to keep him company, an acquaintance from Brunswick attending Howard Law School. But then his mother went home to care for her other children, and the roommate got a place closer to campus.

Finally, the condo was empty, except for Brown and Lopez. Brown looked at his manager. “Are you going to stay over?” he asked tentatively. Lopez, stunned, realized Brown had never spent the night alone before. Lopez took off his shoes.

A Man’s Job

Brown’s naivete poses the question once again: Is it wise for the NBA to make a foray into surrogate parenting of kids fresh from high school? What’s to be done with a Kwame Brown? What is the nature of the league’s responsibility to such a tender rookie? No one is quite sure. “There’s a special kind of care and handling they need,” says Commissioner David Stern. “The overriding issue for me is whether the pressure of life in the NBA might be too much . . . The question is whether he will suffer any permanent setbacks by being tossed in the oil too soon.”

Is it worth the trouble? If nothing else, clubs will take a hard look at the issue from a market standpoint. Brown was just one of three high schoolers taken among the top five, along with Tyson Chandler and Eddy Curry, now playing alongside each other in Chicago. But Duke graduate Shane Battier has been a far more mature and productive rookie for the Memphis Grizzlies, averaging about 14 points a game. Even the Wizards’ own Brendan Haywood, out of North Carolina, has offered more immediate help.

Next to them, Brown’s floundering has been painful to watch. He has been benched, placed on the injured list, and staggered by self-doubt. Only in the last month of the season did he begin to look like he might someday become the starting power forward the Wizards initially projected him as.

Not even the tutelage of Jordan has been able to ease Brown’s entry into the league. Wasn’t Jordan supposed to help guide this rough, raw, young, incompletely formed player into professionalism? Jordan firmly contends that Brown is right on schedule. “My expectations for him were never as high as his, or other people’s,” Jordan says. “He’s never been taught.”

But nobody pretends anymore that this is a fairy tale, unless it is a fairy tale with a cautionary moral. Stern, for one, is convinced that at least a couple of years of college produce happier young men and more fundamentally sound ballplayers. And he thinks that others in the NBA are watching the Kwame Brown saga unfold, and in doing so may find an antidote to irrational exuberance in the trading of player futures. “In a funny way, I think there might be a market adjustment,” Stern says. “That will be ameliorative in its own right.”

Stern wants to know exactly what Jordan and the Wizards expected when they drafted a 19-year-old straight out of high school. “What we’re finding is that a 19-year-old would tend to respond like . . . a 19-year-old,” says Stern. “Who should that surprise?”

At least one person, Collins, is ready to admit that he misjudged Brown’s readiness to enter the league. “It’s not just the education of Kwame Brown,” says Collins wearily. “It was the education of Doug Collins.”

Hard Time

Brunswick, population 15,600, is a place of seedy beauty, that contradictory grace possessed by the Old South, with its decadent residue and peeling antebellum wretchedness alongside old wealth, all of it bathed in sublime breezes. Brown’s childhood home is a clapboard A-frame with torn screens and a collapsing sofa on a sagging porch, as if it all had given way from the weight of holding the eight Brown children and their single mother, Joyce.

Where Brown is from, ordinary career options range from wielding a sponge at a carwash to a spatula at a fast-food restaurant. These are some of the jobs held by his brothers. And then there are the murkier and more tawdry employments that have landed four of them in jail. One of the earliest elements of Brown’s education was simply: Don’t do what they did.

“They made every bad decision that you could possibly make, and I saw the ending result,” he says. “So it was almost like a test that I already had the answer for. All I had to do was fill in the blanks. I just did the total opposite.”

Brown’s oldest brother, Willie James Brown Jr., 29, is serving a 121/2-year sentence in federal prison in Jesup, Ga., for conspiracy to sell narcotics, more specifically, for distributing crack. Tolbert Lee Brown, 25, was convicted of shooting a man and is serving a 15-year sentence in the Wilcox (Ga.) State Prison for aggravated assault. Two other brothers, Alton and Tarik, have had lesser difficulties with the law.

Where Brown is from, religion can be a fairly desperate matter, a begging for some explanation and improbable rescue from the unpayable bills and empty refrigerators and the illnesses that come from living in stagnation and deprivation — in the case of Joyce Brown, the gnarling arthritis, or the kidney disease that left her with just one, or the degenerative disk in her back from cleaning under all those beds at the local Holiday Inn. It was at the urging of Reverend Ike, the television preacher, that Joyce Brown finally left her physically abusive husband, Willie James Brown, once and for all after 17 years.

Joyce Brown met and married Willie, a truck driver from Charleston, S.C., when she was barely 20. She was born and reared in Brunswick; her father was a fisherman and her mother worked in a cannery. Willie offered her a ticket out of town, and to be a father to her first child, Carla Yvette, who is now 32 and lives in Smithfield, Va. Seven more children came in close succession, Willie James Jr., Tolbert, Alton, Tabari, Tarik, Kwame and Akeem.

No one in the family could anticipate when Willie would turn ugly and administer a beating. Joyce Brown is 6-2 and not easily bullied. She tried to leave, she says, “almost every year. I’d get away, and he’d get me right back.” She would flee to Brunswick, and he would come after her, and tell her, “These are my children. They belong to me. You might leave, but you aren’t taking them.” That was his way, she says, of telling her, “You’re not going nowhere.”

She suspected he was using speed when she found a handful of multicolored pills in his pocket, which would have explained his violent mood swings. “There were some good days and some bad days,” she says. “There were some ups and downs. I had to keep my head. The stuff I went through, it was pretty bad. Somebody needs psychological help to get through it. And then, you rely on God. I was raised in the church, so I had to grab my faith, and I started digging deep for the spirit. Because I was in a deep need, and I could have just given up.”

At one point, when Kwame was 5, certain that her husband was coming after her once again, she was desperate enough to write to the Reverend Ike, explaining her situation and asking for help. “What should I do?” she asked.

Some time later, she received a reply. As she remembers it, the TV preacher wrote, “He’s going to kill somebody. But it’s not going to be you. When your mother gave birth to you, she gave birth to an Amazon.”

This time, when Willie appeared in Brunswick, she jabbed her finger at him and quoted the Reverend Ike. “You’re going to kill somebody. But it’s not going to be me.”

In 1990, Willie James Brown was convicted of murdering his 22-year-old girlfriend with an ax handle. He is serving a life sentence in the Evans Correctional Institution near Bennettsville, S.C. Kwame has not seen him since he was 6 or 7, and says he has no desire to.

His father’s absence was a relief for everyone. But it left Joyce alone with a houseful of kids — big, tall ones with large appetites — and no paycheck. Joyce got jobs cleaning rooms at the local hotels. The work told on her back. Every day she would have to shove the huge bureaus away from the wall and vacuum behind them. She would flip the heavy mattresses back and sweep under the beds.

“My mom struggled day in and day out,” says Tabari Brown, 22, a junior and a basketball player at Jacksonville University. “My brothers hated to see her like that.” When Joyce would get her paycheck, she would buy food and pack the refrigerator with it. The boys would pillage it. “When it was gone, it was gone,” Tabari says, “and it was gone for a while. And that’s when my brothers used to have to do that stuff. They’d go out in the streets.”

One evening, early this season, Brown drove to a Wizards game with Lopez in his Mercedes S500. In the midst of a chat about his halting pro career, he suddenly started talking about his childhood. Lopez asked him what his dreams had been.

“Did you ever imagine?” Lopez asked.

“Yeah,” Brown said, “I used to imagine I was full.”

Joyce pleaded with her sons to stay out of trouble, and badgered them to go with her on Sundays to the Church of Greater Works. “It was hurting her, what they had to do to help her,” Tabari says. “She wasn’t too happy with any of that, the whole situation. She’d tell them don’t do that. They’d come back at her like, how you think you going to do without it? She’d cry.”

According to Tabari, the older brothers attempted to shelter the younger boys; it was becoming apparent the younger ones might parlay their athletic talent into an exit. At night, Kwame and Tabari would sneak out of the house and follow the older Browns to the local park, where they hung out. Tolbert would wave them off. “Get out of here, go the other way.”

Kwame was close to his mother. He was her most talkative son, a chatterbox, and a pleaser. He tended to do what she asked him to. “Mama, I’m not going nowhere,” he’d tease her. “You can put everybody else out of the house when they’re 18, but I’ll be here. I’m not going anywhere. I’ll be right here with you.”

“You don’t go to college, you getting out of here,” she’d say.

God’s Work

By the time Brown was a freshman in high school, he was 6-foot-6 and he was already getting recruiting letters from the University of Florida. But he had a temper. In one game, he slammed a wall and hurt his hand when he missed a layup. He also had a tendency toward aimlessness, and his grades were uneven.

Glynn Academy called in John Williams, who runs the Gathering Place, a youth ministry, and who works with troubled kids in the school system. Williams offered Brown a deal: If he got his grades up, he’d let him drive his gray Buick. Clearly, Williams is not your average pastor. He’s not opposed to bribing members of his flock, or manhandling them. He and Brown became close friends; if Brown wasn’t in the gym, he was with Mr. John, as he called him.

His methods with Brown weren’t always gentle. One afternoon, Williams was in the principal’s office when a teacher came in and complained that Brown was supposed to be studying for a major test, and instead was in the gym again. “Can I handle this one?” Williams asked.

Williams found Brown shooting baskets and fooling around with a crowd of people in the gym. He called him over to the sideline.

“What?” Brown asked.

“I need to tell you something,” Williams said.

“Are you going to hit me?” Brown asked.

“I’m not going to hit you. Lean down, I don’t want everybody to hear.”

Brown leaned down. He had just gotten his ear pierced, and he had a small wooden post in his earlobe. Williams grabbed it and twisted it.

“You’re going in that classroom and going to study for that test, and you’re going to pass it.”

The post broke off in Brown’s ear. Williams led him down the hall and pushed him into the classroom. Brown, his ear bleeding and tears streaming down his face, slumped in a chair. He passed the test — eventually he would make honor roll his last four semesters of high school.

Brown grew five inches his sophomore year, and Florida stepped up its recruitment. Williams and Joyce Brown drove him to Gainesville, Fla., and showed him the campus. Williams said, “You can have this if you want it.” Brown committed to play for Florida Coach Billy Donovan.

In Brown’s senior year, it became apparent that NBA scouts were looking at him. He averaged 20.1 points, 13.3 rebounds and 5.8 blocked shots at Glynn Academy. Donovan felt compelled to tell Brown what he knew, which was that he was projected to go in the top five, maybe even top three, if he decided to declare himself eligible for the draft.

“Mr. John, am I that good?” Brown asked.

“Man, I don’t know. Apparently so.”

In January 2001, just as Brown was evaluating whether to make himself available for the draft, he was driving around town with Tarik and one of his cousins when someone shot out the back window of their car. The bullet, he told an Orlando Sentinel reporter, could have hit any of them. “It didn’t have a name on it,” he said.

That spring, Brown declared for the draft. The decision to forgo college meant relinquishing his youth, and he knew it. But what was the option? To spend a couple of years at Florida and maybe risk injury, or a decline in his draft status? Or get another car window shot out hanging around Brunswick on spring break? It wasn’t a difficult choice.

Joyce Brown’s religion comes in a roux with folklore. A woodpecker pecking means that someone on the street will soon die. She believes this as fervently as she believes that it was through her prayer that her son was handpicked by Jordan to play for the Washington Wizards. On June 27, the Wizards made Brown the first high school player ever to be the first pick and gave him a contract worth nearly $12 million.

This was God’s work. “When God put Kwame in that place, it was for this family,” Joyce says. “We had a long, hard road.”

The Wizards, on the other hand, wanted to see less of God’s work, and more work from Kwame Brown himself.

The Wrong Foot

On the day that Brown was officially introduced as a Wizard, he and his mother met with Jordan and Collins just prior to the press conference. Jordan told Brown it was important that he make the right kind of start. “If you make bad decisions, you make it hard for us to get you back on course,” Jordan cautioned him. “So the best thing is to just stay on course. It’s easier to keep you straight than to try to get you back on track.”

The exact opposite happened. Brown was continually distracted by his new status. Brunswick threw him a parade and gave him a key to the city, but life there became so frenzied he couldn’t get any peace. Joyce came home one evening to find her living room full of strangers. “Who are all these people in my house?” she demanded. They were mostly autograph seekers. Brown was back in his bedroom, with the door closed.

He was hounded by neighbors and strangers who wanted favors, or money, or just to hang around. Old friends resented it if he didn’t call or show them enough attention. “Now you think you’re all that,” they said. Every local school principal insisted he come speak to the student body. When he tried to say no, they would scold him for being too good for Brunswick.

“The thing about a fishbowl is, it has no corners,” he says.

He signed endorsement contracts with Adidas, Sprite, Cingular. He suddenly had appearances, interviews and business meetings. He had to hire accountants and managers to oversee his money.

After the draft, Brown went to Gainesville, where he wanted to spend part of the summer working out at the university, with some of his college-bound friends. In a bar one night, he danced with the wrong girl. Her boyfriend took a swing at him. Brown swung back — and injured his hand.

The injury was the first in a series of mistakes that set him back. Collins was on vacation in Illinois when he heard that Brown had hurt his hand. He cut short his trip and returned to Washington, to spend some time with his new protege, and “to try to help him get settled.” Collins discovered that Brown was already having difficulty juggling the demands on him. The first thing he noticed was how much Brown’s cell phone rang. “The phone would ring, and he’d say, ‘This is my brother in prison and he wants money.’ I thought, ‘Oh my goodness.’ “

“Turn that off,” Collins advised, pointing at the cell phone.

Somehow, despite the best intentions on the part of SFX and the Wizards organization, Brown’s entry into the league was disorganized. His lead agent, Arn Tellem of SFX, had dealt with schoolboys before, representing Kobe Bryant and Tracy McGrady. But Brown’s circumstances were unique: No teenager had ever been the top draft choice, handpicked by Jordan, with all of the attendant pressures.

“The truth? There was no plan,” Lopez says. “Kwame is the only one in this situation,” Lopez maintains. “He moved from Georgia, from a very homey, big family. And now he was alone. This is unique.”

Brown listened to too many so-called experts, who told him he needed to bulk up. He gained 20 pounds, ballooning to 255. He reported to training camp in Wilmington, N.C., heavy and already somewhat overwhelmed. He was promptly blasted by Collins for being out of shape. Brown, Collins declared, was probably three months behind “where I want him to be right now because he lost a lot this summer.” Collins’s mood would only get worse.

Brown’s missteps might not have been so irksome if the Wizards’ prospects hadn’t changed dramatically with Jordan’s decision to leave the front office and return as a player. Suddenly, instead of building slowly, over a period of years, the Wizards wanted to make the playoffs now to justify Jordan’s grand experiment. “The whole thing changed,” says Lopez. “M.J. and Collins were two different guys after M.J. decided to return. It’s not negative, that’s just the way it was. Now you didn’t have time to develop this kid; instead it was about making the comeback worthwhile. Now it was, we’ve got to go ballistic to get to the playoffs.”

It was evident Brown would not be able to help them right away, as hoped. The tempo of pro workouts caused Brown back spasms. “He had a bad back, a sore hamstring,” Collins says. “You compound and complicate his task by his horrible condition. Now you start to struggle, lose confidence. And it’s a spiral.”

Collins was increasingly aghast at what Brown didn’t know. There were so many simple things he had to learn: when to lob, when to throw a chest pass, when to throw a bounce pass. Things kids who’ve gone to basketball camps and colleges already know. Like footwork. “He was like a guy who wants to go into high finance, and he only took a couple of classes,” says Wizards forward Popeye Jones.

How was Brown supposed to learn the plays, and the options off the plays, when he didn’t even know proper positioning? “Forget on the NBA level,” Collins says. “We’re talking just basketball.”

He had a lingering adolescent laziness that drove his handlers crazy. So did his childish attention span. At first Collins and Jordan and the rest of the Wizards alternated fatherly speeches on responsibility with gentle needling. But then they began to lose patience.

When Brown twisted an ankle during an exhibition game and untied his shoe on the bench, Jordan said, “Lace that thing up. I’ve played with ankles 45 times worse than that.”

When Collins tried to set up an offense, Brown might giggle or chat with a teammate. “He starts moving while I’m trying to teach,” Collins says. On the floor, he would be totally lost, have no idea what the play was. Collins would have to explain it all over again.

And, like any teenager, Brown always had an answer back.

“But . . .” he would say.

“Just listen,” Collins would snap. “I don’t need you to say anything back.”

Nothing Brown did seemed to please Collins. The man was as spiky as his cropped hair, one minute fatherly, the next screaming with impatience, and then, finally, cold. Every practice was the occasion of a misstep. No sooner would Brown touch the ball, it seemed, than Collins would bark at him.

“Kwame, you can’t play on a railroad track. You have to be able to change speed.”

Brown would just stare back, seemingly uncomprehending. “Kwame, you’re never in a proper position if you aren’t in a position to help. You’re the last line of defense.” He would seem to ignore the simplest directions. Collins would say, “Watch out for the lob, watch out for the lob!” Ten seconds later, a lob would go over his head.

“I wish you would stop correcting me and just let me play,” he implored Collins one day.

“Kwame, you don’t know how to play,” Collins said.

And there was Jordan. He wasn’t the mentor that Brown had expected. With the comeback, he had his own problems, including a sore knee. He could be warm, but he could be hard, too, coolly judging, and demanding. He liked to haze the rookies in small, collegiate ways. Jordan would grab a basketball, and drop-kick it high into the stands and make them run the stairs to retrieve it.

Jordan instructed by example. He would ostentatiously arrive in the locker room early and watch tape after tape of opponents, loudly explaining tendencies to younger players. The underlying implication was, Be Like Mike. “He’s been hard, he’s been stern, he’s been tough,” Brown says.

Brown sprained an ankle in the opener at New York on October 30 and missed the next four games. He started two games in November, but was clearly out of his depth; two points and a rebound was all the Wizards could expect. “Just burning up minutes, trying not to make mistakes,” is how Brown described his performance. “Hopefully, your guy doesn’t score and you won’t do anything to make yourself look bad.”

Meanwhile, the team got off to a wretched 2-9 start. Brown felt helpless, and guilty for not contributing. “It’s hard, because you want to play well and help the organization and you don’t want to come in and let ’em down, and you can’t,” he says. “You can’t step in and step up to the job.”

Brown was vividly aware of how he compared with other high school rookies — he was off to a much slower start than Bryant, or McGrady, or Garnett ever had. He was even lagging behind Eddy Curry and Tyson Chandler, who were playing whole periods at a time for the Chicago Bulls. It was embarrassing; here he was the No. 1 pick, and he wasn’t playing.

His teammates by turns tutored and lectured and scolded. “A lot of people talk at me,” Brown observes. “Very few speak with me.”

By midseason, Brown’s face had broken out. He had circles under his eyes. He was having such trouble breathing during practices that Collins feared he was seriously ill. It turned out he had exercise-

induced asthma, because his lungs weren’t developed enough for his size, and couldn’t cope with the pace of NBA workouts. Basically, he had never worked hard — he simply didn’t know how.

“When are you going to quit being a baby and grow up?” Collins would shout at him.

It was Collins’s job to harden Brown, to teach him how to suffer, and in some ways the process was as traumatic for him as it was for his pupil. “I’m sure he thinks I’m this tough guy,” Collins says. Collins has not enjoyed being the chief villain of Brown’s existence, and his self-doubt is palpable. Popeye Jones observes, “Doug Collins was new at this, too. He had never coached a high school player.” Collins wishes now he had understood just how vulnerable Brown was, emotionally and physically, beneath that big body. “I wish I could throw a switch and go back to training camp,” Collins says. “I wish I could start over.” What would he have done different? “Understand, seen his side more,” Collins says.

“I love Kwame,” Collins continues. “I don’t really think he comprehends how much I care, and he won’t for two or three years.”

Collins was right. Not only didn’t Brown feel cared for, at times he felt isolated. Mostly, his teammates were involved in their own lives. He was lonely. “It’s boring,” he says.

It didn’t help that he was separated from the redoubtable Joyce Brown. After an initial two-week visit to get him settled, she returned to Brunswick. She was only able to visit occasionally. They talked on the phone a couple of times a day.

Washington was disorienting. Accustomed to country lanes, he was confused by the hectic traffic circles and the noise. When he went to breakfast, the waiters looked at him blankly when he asked for grits and cold milk. The Wizards wanted him to rent an apartment near MCI Center, but he couldn’t bear the idea. He restricted his movements to a triangle, from his condo, to the arena, to Lopez’s SFX office in Friendship Heights. There was no one else in his circumference. He felt apart from his old friends back in Brunswick. “I don’t talk to people like I used to, because they can’t relate.” He felt the same about his new teammates. “Me and them, we can’t even go to the same places.”

He wasn’t old enough to go to clubs or bars, and though Jones, Christian Laettner and Duane Ferrell befriended him, they were a minimum of 10 years older, and they weren’t exactly into PlayStation, as he is. Brown brightened up briefly when his brother Tabari visited from Jacksonville. Lopez drove them out to a mall in Anne Arundel County that had a huge game arcade. They bowled, played race car games. It was a rare carefree night.

Brown came off the bench on December 4 to record the first double-double of his career against San Antonio’s David Robinson and Tim Duncan, with 10 points and 12 rebounds. The Wizards hoped it was the start of something. But the next day, typically, he came to practice lethargic. By now Collins had had it, and so had most of his teammates. Jordan was struggling with a bad knee and doing everything he could to help turn the team around, and here was this kid who didn’t know the meaning of work.

It was Brown’s worst day as an NBA player. “The most physically demanding day of my entire life,” he says. Collins put the Wizards through a brutal, exhausting practice. The team was in a collective foul mood. Despite Brown’s mini-breakthrough, the Wizards had lost yet again. “Everyone was arguing, people were beating each other up,” Brown says. But mostly, they took it out on him.

Brown couldn’t do anything right. “He couldn’t catch it, couldn’t throw it, couldn’t shoot it right,” Jones says. In a series of three-on-three drills, the Wizards banged him — hard, intentionally. “He got pretty beat around,” Jones says. Center Jahidi White knocked him to the ground — and fell on top of him. Brown lay there, stunned and bruised.

“Get up, you aren’t hurt,” White said.

Brown got up, aching, holding his back. His gray practice shirt was soaked through. Nobody had any sympathy for him. Not even Popeye Jones, the veteran who’d looked out for him the most. “It’s time for you to grow up,” Jones told him, coldly. “Now. Today. Stand on your own two feet.”

Collins, still not satisfied, ordered a set of punishing sprints. Brown hesitated. “I hurt my back,” he said.

Collins wheeled. Now it was his turn. “Stop being a baby and start growing up and playing, and earning the respect of your teammates,” Collins shouted. “They’re tired of you. They’re tired of you getting knocked down, and laying around. They’re tired of you holding your back. And holding your head. And holding your thumb. You’re the one who has to be in that locker room, and meet them eye to eye.”

Brown stared at his feet. “Do you want to play or not?” Collins snapped. No answer.

“Get off the court,” Collins said disgustedly.

He sat in front of his locker trembling and crying. This is it, he thought, the league’s not for me. I’m horrible. The coach thinks I’m horrible. The whole team thinks I’m horrible. I can’t even play. Then he got on a treadmill and ran as hard he could, for almost an hour.

After a while, Jordan came into the locker room. He sat on a bench with Brown, and put his arm around him, and hugged him. “You’re going to be all right,” he said. For several minutes, he talked to Brown in soothing tones. “Doug is tough, but in a few years you’ll understand how good he is,” he said. They still believed in him, Jordan affirmed. “We put our necks out for you,” he said. “We think you have the ingredients to be a great power forward for a long, long time.”

To Brown, it meant everything. “He showed me a side you never read about,” Brown says. “The M.J. who comes over and picks you up and talks to you when you’re down and out.”

Dunk and Hope

That day turned the Wizards around — they won their next nine games. But Brown’s recovery wasn’t so immediate. Collins made a decision to back off. Anyone could see how it was wearing on the kid. “His face was broken out and he looked horrible,” Collins says. One night, Collins said to his wife, Kathy, “I’ve got to take the pressure off him.” He decided to put Brown on the injured list. The excuse was a sore calf, but the real reason was that Collins wanted him to decompress.

Jordan, too, did all he could to take the heat off Brown. In his public statements he tried to lower the bar. “The expectation was set before Kwame understood the magnitude of it,” Jordan said. “He wants to live up to it, but wanting, and having the tools to do it, are two different situations. To throw him out there when he doesn’t have the tools yet would be a mistake.”

Jordan understood better than anyone the embarrassment factor. Chandler and Curry were being showcased in Chicago, “but those guys aren’t winning, either,” Jordan said. “In the long run he’ll be better off than those guys, by being able to learn about sacrifice and the components of winning, than scoring 20 points for a last-place team.”

Brown spent a long stretch watching from the bench. At first, he viewed it as a punishment. But it worked. He could learn at a slower pace, without a sense of guilt or urgency. He practiced hard with the team and lifted weights. The press forgot about him for a while, and no one asked him why he wasn’t contributing more, or compared him with Chandler and Curry. Gradually he started feeling better about himself. “I think the best thing we did was shut him down,” Collins says now.

When he came back, he was a more relaxed player and a more consistent one. Collins, too, was gentler with him — though no less demanding. On a road trip to Boston, Collins called Brown to his room, and they talked for more than an hour. “You got to help me, I’m failing here,” Collins said. “I haven’t been able to bring out the best in you.”

Brown pleaded again to be allowed to just go out and play, to stay on the floor and fight through his mistakes. Collins said, “Okay, I’m going to put you out there.” On March 10 in Boston, Brown had one of his best sequences of the season — he scored eight points in a five-minute stretch in the second quarter. “He showed he could carry an offense all by himself,” Jones says. “At 19, he carried us for a five-minute stretch. It was a joy to sit on the bench and holler his name.”

But the very next night he had four quick turnovers in the first half. Collins benched him in the second. Afterward, Collins lectured him about being dependable. He would use playing time like a parent, Collins said. “The more I can trust you,” he told Brown, “the later I’ll let you stay out.”

But the setbacks were temporary. Against Portland five days later, Brown put together another flashy performance. He was provoked by the Trail Blazers’ Rasheed Wallace, who ragged on him as they ran up and down the court.

“Come on, show me why you’re the No. 1 pick,” Wallace said. Brown answered — he blew by Wallace for a baseline dunk. He ran upcourt with a huge grin. “Okay,” Wallace said. “All right.”

Against Denver on March 20, he had eight points, five rebounds, one assist, a steal and a block — all in just 17 minutes. At one point, with the Wizards desperately needing a win to keep playoff hopes alive, Brown made one of his most confident plays of the season. He went up for a shot and got hit in the head. Once, he would have fallen down and grabbed his face. Instead he gathered himself and went up and scored. Collins looked down the bench and said, “That’s growth.”

After the game Collins added, “You might think of it as one basket. But to me it was much more than that.”

Such stretches had Brown and everyone around him beaming. “I’m starting to see light at the end of tunnel, and I think there’s going to be a rainbow there,” Collins said. Jordan was also bullish on Brown. “I see signs. He’s freshly confident,” Jordan said. “I see his smile and I know he’s enjoying it.” Brown even kidded Jordan about being able to dunk on him. “I like that,” Jordan said approvingly.

So . . . had he dunked on him?

“He hasn’t come close,” Jordan said.

A New Man

As important as his improvement on the court has been, there are also signs the No. 1 pick is learning to manage his affairs off of it. He is taking better care of himself. He still hits takeout joints, but now he frequents the salad bar at Wendy’s instead of eating fried chicken at Popeyes. “We’ve talked about baked, not fried,” Lopez says. He no longer carries his bottle of French dressing.

“He’s learned vinaigrette,” Lopez says.

He is newly mature in his dealings with Collins. “He wants me to do so well, so bad, that sometimes things come out wrong,” Brown says of Collins’s past blowups. “But in the end he always comes back and tells me, ‘I’m doing this to help you,’ and I believe him. I don’t think he’s continually trying to hurt my feelings or make me mad.”

Toward the end of the season, when Collins explained something to him, Brown moved over one seat, leaned closer, made eye contact and nodded his head. Also, he decided to turn off his cell phone on game days. “It’s just time and work,” he says. “I’m finally at peace.”

So was it worth it? The yelling, and the doubts, the injured feelings? Personally, Collins isn’t sure. “I don’t want to do it again,” Collins says. His nightmare is that Brown will end up hating him. He thinks about Tracy McGrady, and how he struggled as a rookie in Toronto. Finally, after three years, McGrady left Toronto and went to Orlando, where he finally became . . . Tracy McGrady.

“My biggest concern is, you develop them, and then they go somewhere else,” Collins says. “You put three years into them, and they resent it. And about the time they’re ready to be stars, they leave you.”

But Kwame Brown’s education is far from complete. Everyone agrees this summer will be critical for him. Instead of going to Gainesville to hang out — he has bought a $400,000 house there and intends to eventually take some classes — he will have a work-intensive off-season. He’ll go to Boston to play for the Wizards farm team in an NBA-affiliated summer league for first- and second-year players and aspiring draft picks looking to hone their games. He will spend some time in Chicago training with Jordan. And he will attend two clinics, the Pete Newell Big Man Camp for college and pro players who want to work on their fundamentals at the center and forward positions, and an agility and footwork clinic in Phoenix.

He has also promised that he will be more responsible this off-season than last. “It will be very interesting,” Collins says.

The summer will be shaping for him from a personal standpoint as well, according to his business manager. “The most important part of his education has not happened yet,” Lopez says. It will happen in the off-season. “That’s where he will become the man he’ll become.”

He needs, for instance, to get his family’s financial affairs more organized. He has placed his family on an allowance, and while he wants to help them, he is leery of creating dependents. “I’ve told them I’m willing to help them in any way, if they’re willing to help themselves,” he says. He continues to be dismayed by the effect his wealth has had on some of his old friends and relatives. “It’s the people close to you who are affected by it the most, and that hurts you the most,” he says. “They just automatically assume you’re some kind of vending machine full of money that never runs dry and you’re supposed to do things for them. And you can’t do that for everybody, because you’d be broke.”

For example, there is his father. Recently, Brown got a letter from him. He was proud to see what his son had done, his father wrote, and he had found faith. Brown had mixed feelings as he read. “He sounded like some kind of Muslim priest,” he says. Then he got to the part where his father accused his mother of stealing the children.

“I guess he thinks I don’t remember what happened,” Brown says. “But I do.” And then came the inevitable paragraph. “Of course,” Brown says, “there’s that part where he says, I don’t need anything from you, but could you send money?”

Brown waved the letter at Lopez. “Can you believe this guy?”

There is one person Brown takes great pleasure spending money on, and that’s his mother. He purchased a new home for her, a sprawling white stucco affair in Oak Grove Island, a gated community just outside Brunswick. He also arranged to help her furnish it. They bicker over the details.

“You should listen to me,” he says. “You need me to tell you what to do.”

“Boy, I didn’t come out of you,” she says. “You came out of me.”

Joyce shows off the new house as if it were a museum. She marvels at the endless closets. The master bath is her pride. “Look at this shower,” she says. “Big as a locker room.” She calls it “my peace house. I come here for peace.”

But the house remains sparsely furnished. To Brown’s astonishment, the old house is where Joyce still spends most days. Oak Grove Island is clean and beautiful, with emerald grass and spewing fountains, and the obligatory golf course, and joggers. But all of her friends are in the old neighborhood, and she doesn’t want to move her youngest, Akeem, from his school. Brown can’t get her to sell the old place. “I don’t know how I can get her away from that house,” he laments.

It’s a small problem, compared with the old ones. At least, Brown says, the family is no longer desperate. It is on this point that any lecturing do-gooders who think Brown should be in college must yield. It is inevitable: Boys will offer themselves up to the pros too soon, and men will draft them, for better or worse. Brown says he has no regrets. “College is supposed to prepare you for a job,” he says. “That’s why you go to college.”

He’s already got the job. Now he just has to succeed at it.

“I can do it,” he says. “I was born alone. So I’ll be all right.”

Sally Jenkins is a Post sports columnist. She will be fielding questions and comments about this article at 1 p.m. Monday on www.washingtonpost.com/liveonline.

No Comments so far

Jump into a conversationNo Comments Yet!

You can be the one to start a conversation.Only registered users can comment.